12 December 2015

Minimalism Pre-Prints 3: Structure, Repetition, and Reception in Einstein on the Beach (2)

It Could Be Very Fresh:

21 November 2015

Minimalism Pre-Prints 2: Structure, Repetition, and Reception in Einstein on the Beach (1)

Note

It Could Be Very Fresh:

Structure, Repetition, and Reception in Einstein on the Beach

(1999; part 1)

Structure of the Opera

2 Throughout this paper, small caps will be used to denote motives in the opera. These motives can be found in charts in the appendix.

Addition of Wilson's Comment

Visual and Non-musical Structures

To be fair, ‘Einstein’ was a co-creation of Mr. Wilson and Philip Glass, the composer. But most people not only saw it as basically Mr. Wilson’s work—so much so that Mr. Glass was openly aggrieved, and has declined further collaboration with Mr. Wilson—but as the capstone to a series of remarkable large-scale Wilson theatrical creations that dated back to the 1960s. (New York Times, 26 November 1978, p. 5)

The transformations of the train into building and spaceship in Act 4 also have their roots in relativity thought experiments. The building, seen from both the front and side simultaneously, is a demonstration of how observers at rest see light reflected off objects moving at high speeds.11

The spaceship image, in addition to being a standard demonstration of relativistic length contraction (along with a rotating ruler or stick or an oblong clock which are also seen in the opera) hints at the prospects for future nuclear apocalypse which Einstein’s work on nuclear physics made a frightening possibility.12

The length contraction demonstrated by the spaceship manifests itself in several other ways in the opera. The tall, narrow chairs used throughout the opera are examples of this physical phenomenon on stage. Further analysis of how the staging parallels the teachings and life of Einstein will have to await a video viewing of the opera.

Minimalism Pre-Prints 1: Ambiguity and Certainty in Minimalist Processes

Preface

Ambiguity and Certainty in Minimalist Processes

Dublin Conference on Music Analysis, June 2005

20 November 2015

Peer-Review and Publication of Unprintable Materials

In thinking about the future, I find it’s always helpful to reconsider the past. What were the roles of publishing in the age of print and print only? Why was it important to have ideas published? [Back then], only publishers could get an idea out to a large audience that would want to read it. Publishers had distribution networks that could take it from a single location (the city that we still cite in footnotes) and make it available throughout the world. The publishers took on financial risk in printing and distributing material: if they did not print ideas that were worth reading, scholars and librarians would stop subscribing to journals or purchasing books, leaving them unsold inventory in the present and less influence in the future. The publishers’ sense of the market would give an idea of how much interest there would be in the idea while peer review would ensure the quality of that idea. Initially, the reputation of a journal or publisher would determine how many people purchased and read it. Later, public review would help individuals and libraries decide which material to pick up after the initial sales.

Errata: 2015-11-20: The original version of this post mistakenly identified the third committee sponsoring the session. It is the Committee on Publications. It also referred to a slide of parallel perfect consonances in Bach chorales that was not included. The text has been adjusted.

08 August 2015

Merge upstream into your fork in GitHub

For years I’ve been trying to get student assistants to use GitHub more effectively to work on larger projects. One of the main problems though has been that the process of using forks + pull requests to submit their code to the main project has always required going back to the terminal for one key step: pulling and merging others’ changes from the upstream branches. Today even for many seasoned programmers, the terminal/command prompt is a bit of a mystery to students. Thus it would be great if the GitHub graphical client made this simple or at least possible.

The most recent versions of the GitHub client (at least on Mac; untested on Windows; I’m on v. 208) don’t exactly make the process simple, but at least they make it possible.

Open the GitHub client and if you haven’t worked on the project in a while, hit Sync. You should see your own fork; I’ll assume that you are working on the “master” branch and want to merge changes from the upstream (main project) master branch into your own branch.

Your screen should look something like this. (I’ll be demoing on the amazing Latin dictionary program “whitakers-words”[*] which I do not have commit access on, so it’s like what my contributors to my projects would see). All I’ve done is created a little demo text file.

Next I’ll pull down the tab on “master” and switch to the main developer’s master, “mk270/master” (third from bottom).

Click “Sync” in the upper left hand corner to copy it down. The sync button will turn into a progress bar:

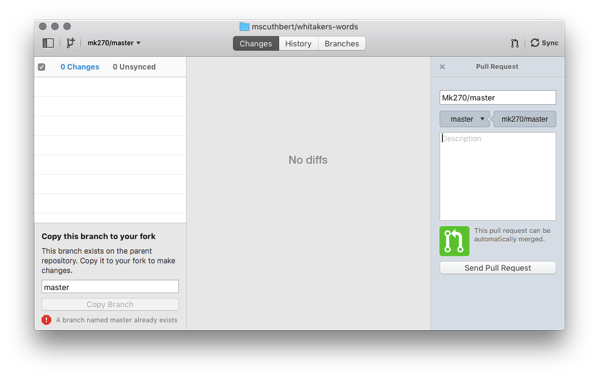

This actually creates a temporary branch confusingly called mscuthbert/mk270/master (or YOURNAME/THEIRNAME/BRANCH) but will just be displayed as mk270/master on the GitHub client. No matter. Now click the button next to the progress bar to create a pull request. You will want to pull from this branch to your master branch (the one marked default branch):

You can leave the description blank since you’re just making a pull request to yourself. Go ahead and click “Send Pull Request”.

Click the link below the “Good work!” button to open up GitHub in your browser. You should see something like this:

Scroll down to the bottom and you’ll see this. Go ahead and click “Merge pull request” then “Confirm merge”.

Now you’ll see the option to delete this branch. Go ahead and do it. You are actually deleting “mscuthbert/mk270/master” not “mk270/master” — I hope it won’t let you delete the upstream master!

After doing so you’ll see this confirmation.

Now return to the GitHub client and switch back to “master” if it hasn’t already put you back there.

Go ahead and click “Sync” again for good measure. Then you can check your History and see that you have all the most recent upstream commits:

Ta-da! Well, assuming that there aren’t any conflicts or anything of that sort. In a case like that you’ll probably still need to get out the ol’ command-line tools, so you will still need to be a bit familiar with them (or have a friend who can help you out). Hopefully the next version of GitHub for Mac/Windows will make this much easier. But for day-to-day work, it’s now possible to stay in sync with the main repository on a more regular basis for people who use the graphic interface tools almost exclusively.

[*] edit August 10: EEK! Autocorrect originally changed “Whitaker’s Words” to “Whiskers-Words” — Fixed! That app only does Cat-latin (catin?): maumo, maumare, maumavi, maumatus V (1st) 1 1 [GXXEK] — meow;” not what we want!

06 August 2015

NL vs. AL leadoff hitters

Often while marveling at Ricky Henderson’s amazing stats, I wondered how much greater a leadoff hitter he would have been if he had spent his whole career in the National League. He had 11,180 plate appearances in the AL but only 2,166 in the NL. In both leagues, the leadoff hitter leads off the first inning, but is not guaranteed to bat leadoff in any following inning. However, I figured that in the National League, batting after the pitcher, it’d be substantially more common that the person batting first in the order would get to lead off. The pitcher almost always makes an out, so I figured it’d be pretty common for him to make the third out (and because of situations where the eighth batter is walked to get to the pitcher, probably more common than one in three). The eighth batter isn’t that strong in the AL, but a lot stronger than almost any NL pitcher.

I’ve been working off and on over the past two years (more off before getting tenure, more on after getting tenure) on an extremely flexible python toolkit for examining baseball games and it finally got to the state of development where I could test my findings. I’m not ready to release the toolkit yet (it needs to be polished enough that I’m proud of it), but here’s the code I used to work:

gc = games.GameCollection()

gc.yearStart = 2000

gc.yearEnd = 2014

gc.usesDH = True

allGames = gc.parse()

totalPAs = 0

totalLeadOffs = 0

for g in allGames:

for halfInning in g.halfInnings:

for p in halfInning.plateAppearances:

if p.battingOrder == 1:

totalPAs += 1

if p.plateAppearanceInInning == 1:

totalLeadOffs += 1

print(totalPAs, totalLeadOffs, totalLeadOffs*100/totalPAs)

It gets a collection of games where the DH is used or not used, looks at each game, then at each half inning, then at each plate appearance. If the batter is #1, then it checks whether it’s the first appearance in the inning, then prints out the percentage of all batter #1 plate appearances which are leadoffs. The results were surprising to me.

| PAs | Leadoff | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No DH | 183,033 | 75,364 | 41.2% |

| With DH | 163,1781 | 63,451 | 38.9% |

The average difference in the percentage of leadoff plate appearances between the two leagues (accounting for interleague games) is only about 2.5%. This works out to about 15 PAs a year different for Ricky in his prime. So one hypothesis down, but many more to be investigated soon.